Medical

Knowledge

From experimenting with popular healing to using the populace and their bodies in research, medical knowledge in Brazil was intrinsically related to the relationship between medicine, scientific investigation and the population.

1854

In 1854, the judge Henrique Velloso de Oliveira published a translated version of the German botanist Karl Friedrich Phillip von Martius’s book on Brazilian medicinal plants named Systema de Materia Medica Vegetal Brasileira. In it, Martius described how his book incorporated popular knowledge from native groups from Brazil, as well as from African descendants in the country to help advance medical knowledge based on Brazilian plants.

He decided to do it not only because popular healing methods were backed by the communities he visited, but also because doctors himself prescribed popular methods of cure, especially if they lived far away from cities where European medicinal ingredients were more accessible.

He himself had been healed from an ulcer by an indigenous healer: “I cannot forget about malign ulcers that for months had resisted the treatment of doctors, and in a short 48-hour period they had changed completely after a humble healer from an indigenous group treated them with an application of freshly collected herbs.”

I cannot forget about malign ulcers that for months had resisted the treatment of doctors, and in a short 48-hour period they had changed completely after a humble healer from an indigenous group treated them with an application of freshly collected herbs.

— Karl Friedrich Phillip von Martius

POPULAR HEALING

WHEN WESTERN MEDICINE HAD NO CLEAR ANSWERS ABOUT THE DISEASE

Popular healing was very common, especially when medicine lacked answers for the diseases of the time. During the cholera epidemic, the former slave and healer Pai Manoel gained notoriety among the popular classes in Pernambuco for his concoction against the disease in 1856.

The popular pressure for the local government to support the healer and his methods when medicine had no clear answers about the disease led to serious frictions between the provincial presidency and the public health council because of the provincial decision to let him heal at the navy hospital of Recife.

Pai Manoel's Cholera Treatment Recipe Published In 1856

source: Diario de Pernambuco

1856

His concoctions made the people hopeful, as they believed he would save them from the danger of cholera.

— Unknown "Admirer of the Presidency"

DISEASE AND WAR

HOW DOCTORS BATTLED SCURVY AMID THE PARAGUAYAN WAR

1867

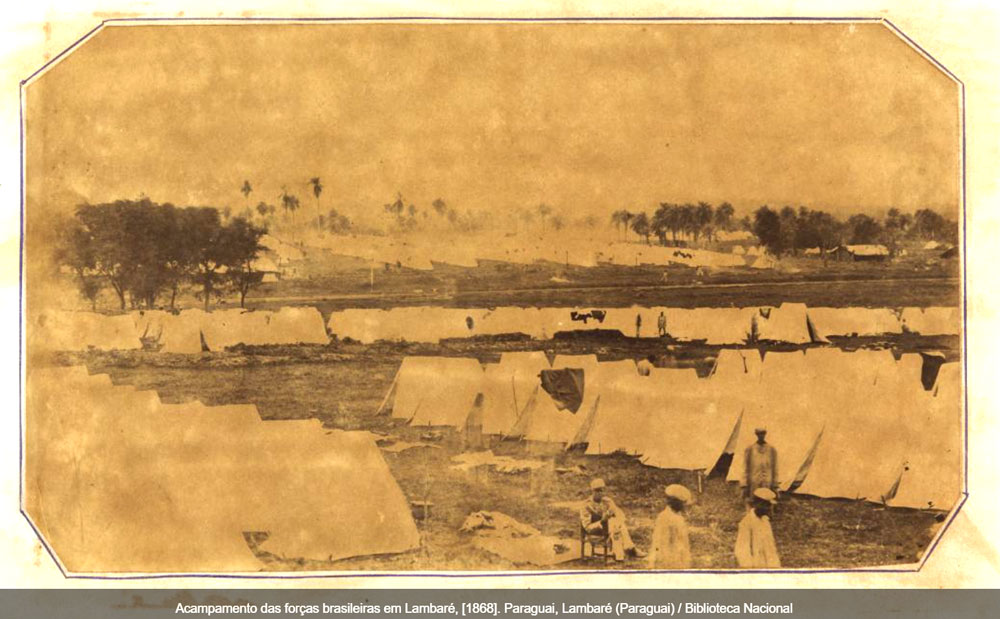

In the 1860s, when Brazil was at war against Paraguay, physicians began discussing the rise in scurvy cases among Brazilian troops. In general, there was an overall acceptance that a poor diet was a reason for scurvy, a deficiency in vitamin C that caused multiple symptoms including bleeding gums, lack of energy and irritability.

Scurvy was then discussed within the realm of labor during the war because it was noticed that soldiers were becoming sick at a much higher rate than their officers. Yet, Brazilian physicians considered scurvy to be more than a disease associated with poor nutrition, and enforced its relationship with class by stressing its connection with people who worked excessively and lived in unhygienic environments.

Within the reality of the war, physicians blamed the Brazilian losses on the government’s neglect toward the health of soldiers, since “diseases are more terrifying, deadly and damaging than the bullets and swords from enemies.”

Diseases are more terrifying, deadly and damaging than the bullets and swords from enemies.

— Dr. Nicolao Moreira

BERIBERI OUTBREAK

ETHICAL RESEARCH AND THE BERIBERI OUTBREAK OF 1871

1871

A breakout of an unknown disease in Recife’s detention center in 1871 led to questions over methods of scientific investigation. As detainees became sick and others began to die, a commission the government created concluded that they were suffering from beriberi, a disease that caused paralysis.

However, local Dr. Carolino dos Santos,who was not a part of the commission, raised serious questions about the moral aspects of research involving the detainees. Within this context, the bodies of the poor were serving medical goals for investigation while raising discussions over ethical methods of scientific research.

First, he was not convinced that the commission had enough knowledge to make a claim just two days after its visit to the detention center, a claim that could lead to panic inside and outside the center.

Second, he complained that autopsies of victims were being conducted in front of the detainees. Those men were not only scared about their health prospects, but were also terrified of seeing doctors opening up their colleagues so unceremoniously.

Recife's Detention Center circa 1880

source: Brasiliana Fotográfica

I must remind the noble medical commission to remove the autopsies from the sight of the detainees (...) because the horror noticed in each of them due to the epidemic and the spectacle of seeing their partners being dissected and mutilated...is such a lack of charity in this Catholic country...

— Dr. Carolino dos Santos